by Gianni Valente

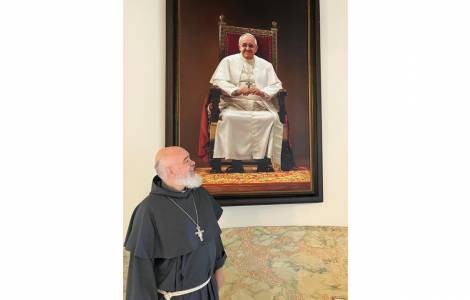

Pope Francis called him to head the old episcopal see of Ispahan, erected in 1629 after changing its name to the Archdiocese of Tehran – Ispahan of the Latins. And he decided to create him Cardinal, on Saturday, December 7, in the consistory. Father Dominique Joseph Mathieu is 61 years old and a member of the Conventual Franciscan, and he is the first cardinal with a diocese in Iran. He has no special "titles" that would have predestined him in any way for this office. He did not prepare his whole life to take on this unique, delicate task. And yet, now that he looks back, everything falls into place and is rearranged in his eventful life. In the flow of memories, details that at first glance seemed insignificant appear to him as important nodes on this path. And each step, he says today, "seems to have prepared me in some way for the event I am now experiencing."

ABBEYS, MONASTERIES AND BORDER AREAS

Dominique Joseph was born in Arlon in French-speaking Belgium and grew up in Flemish Bruges, the "Venice of the North." When he thinks back to the countries of his childhood and youth, he also remembers the monasteries and large abbeys, such as those of Orval and Zevenkerken, which he often visited with his family. And he is immediately confronted with the invisible linguistic and cultural divides that also separate people who are destined by history to live in the same corner of the world. In Bruges, Dominique served as an altar boy on Sundays until he was 20, even in the cathedral. He attended mass every day with some schoolmates. At the beginning there were about ten of them, and by the end of his school days there were only a few left. At some point, the Mass was no longer celebrated due to a lack of participants. "I was 13 or 14 years old," Archbishop Mathieu recalls today, "and I went to the school headmaster to ask if daily Mass could be reinstated. The priest then came back in the afternoons when classes were over and celebrated a Mass especially for the students. He did this for several years, and often I was the only one present at the Mass. When I think about it, It still strikes me. It was a very powerful testimony. Now I celebrate Mass alone too. And then I think of that priest who celebrated Mass for so many years for just one person, and he did it for me. I then tell myself that neither he nor I have ever celebrated alone, because the Mass is always celebrated in communion with the whole universal Church. That is the Church."

JESUS AND THE STARS

The future Archbishop of Tehran combined his Christian path with his passion for astronomy from a young age in Bruges. He received his first telescope at the age of 12. At night he would observe the sky and the stars. "But they were like two parallel lines that ran separately. Until the day I realized that even scanning space filled me with wonder and gratitude for the wonders of God." Since becoming a bishop, Father Mathieu has put astronomy on hold for a while. Too little time and too complicated to take instruments to observe and photograph the stars. But he is surprised to find himself living in the country where the priests of antiquity looked at the sky from the Ziggurats. And for the faithful who are with him today, he puts his other passion, gastronomy, into practice, preparing sweets and good things to eat.

THE INTERTWINING WITH THE FRANCISCAN ORDER

"I was born on June 13, the feast of Saint Anthony of Padua," says Father Dominique. And for him, this is only the first sign with which the Saint of Assisi wanted to launch his vocation into the great family of the sons of Saint Francis. Monasteries, encounters with Franciscan stories and epics, such as those of the Capuchins who lived in Arlon, his hometown, and other places in the hills to keep watch and raise the alarm in case of fires. In his grandfather's room, he found the books of a distant relative who had been a Capuchin missionary in Congo. "I read with passion the stories of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in Canada and those of the Jesuit missionaries in China. But the book that impressed me most was an old volume on Saint Francis of Assisi with yellowed pages." A Dutch priest sent him material about the Franciscan Maximilian Kolbe, who was murdered by the Nazis. At the age of 16, Dominique spent Holy Week in the Franciscan convent in Leuven. These are the years after the Second Vatican Council, when religious life was searching for a new identity. There are tensions and fierce dialectics. "In the refectory, I happened to see priests arguing among themselves, and that did not bother me, on the contrary: it meant that we were down to earth and the priests showed themselves as they were, they did not want to present a rosy image of themselves and monastic life."

When he entered the religious community, Father Mathieu chose the Conventual Franciscan. During his period of formation in Belgium, he was not short of challenges. In Flanders at the time, there was a growing hostility towards the French-speaking Flemish, who were seen as an aristocracy that had made other compatriots suffer in the past. "Over time," adds the Archbishop of Tehran, "I also reconciled myself with this tense period, which helped me to take note of diversity and even conflict, without having prejudices against peoples and cultures."

Dominique Joseph was the eldest son and had two younger sisters. "My parents told me that they were happy about my vocation, they never stopped me, but they told me: if you see that things are not going well, remember that you can always come home. At first, that worried me a little. Then I realized that the greatest sign of their love was precisely that they always left their door open."

After his novitiate in Germany, Father Dominique also remembers the time in Rome, where he spent a lot of time in the Regina Coeli prison, where his confrere Vittorio Trani, who had been a great witness of the mission among prisoners for 50 years, worked as chaplain. "There were several Muslim prisoners," recalls Archbishop Mathieu, "and we wanted to do something so that they had a place to pray in prison. This was a new problem. We procured prayer mats and the Koran, which were made available to us by the Ethiopian mosque. This worked for a few weeks, then the fighting began. Those who had to manage the initiative logistically at the time did not know the difference between Shiites and Sunnis sufficiently... Back in Belgium, I was also interested in the religious practice of Muslim prisoners there, but the problem had long been solved there, everything was already strictly regulated, and we Christians could not even have contact with Muslims to help them. At that time I went to the mosque to study Arabic literature...".

MISSION IN TIMES OF SECULARIZATION

After his ordination, Father Mathieu returned to Belgium and lived the missionary aspects of his religious vocation in a country marked by secularization, where the "deforestation of Christian memory", as Belgian Cardinal Godfried Danneels put it, was strongly felt. Today he remembers: "For a long time there were no vocations, and there was a huge gap between me and the generation before me. In this situation, I knew that I would never receive an invitation to leave for the mission. Because the mission was there." It was about accepting the reality of things. The given circumstances. Father Dominique became provincial vicar and later provincial, while the number of brothers decreased. There were mergers, transfers, closures of religious houses. It was decided to bring the conventual Franciscan together in the house in Brussels where they had their monastery in the immigrant district. In order not to close the Belgian province, the support of the other conventual religious provinces in Europe was requested. "We looked for ways to deal with the consequences of secularization and globalization." Lay men and women gathered around Father Dominique. A community that even then "showed that it needed its freedom" in order to continue to grow on its path.

THE LEBANESE SURPRISE

In 1993, the future Archbishop of Tehran travelled to Lebanon for the ordination of César Essayan, his fellow student and then Apostolic Vicar of Beirut for the Catholics of the Latin Rite. After the civil war, Beirut was still in ruins, with tanks everywhere. Nevertheless, he was impressed by the strength of the poorest people who stayed in the country to endure all the suffering without being able to emigrate, and by the faith of the people he met in the pilgrimage sites. Ten years later, after a long period of hard work in Belgium, his life opened a new chapter when he agreed to go to the land of Cedars.

"On my trip in 1993, I had seen that there was potential in Lebanon for accompanying young people in their growth. In Beirut, I found a job in a French-speaking parish where I was able to start pastoral work straight away." In Lebanon, he also took on the role of Master of Novices. And he experienced the joy of being able to resume the rhythm of community life that he had had to give up during the years of mission in Belgium. In Lebanon, he witnessed the tensions between the country, in particular Hezbollah-Amal, and Israel ("I saw the drone flying over the country in the Bekaa Valley and when I was doing astronomy, I calculated that it passes every 52 seconds"). It was still in Lebanon that he learned for the first time that the Vatican was considering the possibility of asking a Franciscan to go to Iran as bishop.

A NAME FOR IRAN

In 2019, the General of the Conventual Franciscan asked Father Mathieu to return to Rome as Assistant General to the General Curia in the Basilica of the Twelve Holy Apostles. During these years, after the sparse presence of Latin Rite religious in Iran had dwindled between 2015 and 2018, the Holy See's proposal to the Conventual Franciscan to appoint one of the brothers to be sent to Iran remained on the table until the General of the Conventuals finally informed him that he had proposed his name in response to the Holy See's request. But it was the first months of the coronavirus pandemic and Father Dominique Joseph fell ill with a serious form of lung infection. Today he recounts: "I had a relic of Saint Charbel with me that I had brought from Lebanon. I said to myself: if I die and the Lord takes me, I won't have to think about all this anymore. So in any case, I won't decide for myself. Instead, Father Joseph Dominique recovered. Still in poor condition, he went to the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, where the superiors thanked him and told him that "the Holy Father was very pleased" with his willingness to go to Iran. "To be honest," said the Archbishop of Tehran-Isfahan today, "I had not officially communicated any consent on my part. I did not say yes or no. There was only the thought that I had when I imagined that I could die, and I had put the decision in the hands of the Lord."

NON-COMPLIANT

Dominique Joseph Mathieu was appointed Archbishop of Tehran-Ispahan on January 8, 2023. In his new adventure, he knows that the Fraternity of the Conventual Franciscan is behind him and supports him: "Often," admits Father Mathieu, "when we speak of the Friars Minor, we place more emphasis on 'minority' and poverty. In reality, we should also put the emphasis on fraternity. We are first and foremost a brotherhood.” In Tehran, he has no priest to assist him in his pastoral work. And unlike Catholic churches of other rites, the Latin Rite Church has no legal recognition and no defined juridical status. This is also why meetings with government officials are sometimes difficult. To form a legally recognized association, at least 15 Latin Catholic Iranian citizens are required, and the members of the Latin Rite Catholic community in Iran are currently mainly foreigners, embassy staff, migrant workers from the Philippines, Korea and other countries. So today, Father Dominique Joseph hopes that the cardinalate he has received will serve above all to open doors and intensify his attention from the Iranian authorities, and to deepen relations and contacts also through the channels between Iran and the Holy See, which have always remained open since the revolution. There is a particular continuity in relations between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Holy See, which resists all anti-Iranian campaigns and the propaganda spreading in the West. "In the course of my life," said the Archbishop of Tehran, "I have learned to live in borderline situations, to recognize diversity and to move away from stereotypes and clichés when looking at people and peoples." "Certainly," continued Father Dominique, "the people of Iran are very welcoming and I find that it is a country full of contrasts, far from the caricatures that circulate."

CLOSED DOORS CAN OPEN

In Iran, Latin Rite Catholics are a small flock. About 2,000 people, of whom at least 1,300 come from the Philippines. Small communities that raise questions about the meaning and horizon of the mission, about the decision to maintain a presence and even a diocese in this situation. The Archbishop of Tehran-Ispahan does not hesitate. “A brother of mine told me about a person who, before becoming a Christian, spent more than 10 years in front of the closed door of an Armenian Church in northern Iran. When you pray in front of a door, you realize how important it is to be there. A door is a door, even if it remains closed, and sooner or later it can open to show Christ's love for everyone, with gestures rather than words, as Saint Francis showed us". In the meantime, the work to which Father Dominique devotes time and energy is included in the elementary dynamics of ecclesial life: the Masses, catechism, the celebration of the sacraments, the works of charity. The same dynamics that he had experienced in the everyday life of the days in the monasteries and beguinages of Belgium where he grew up. (Agenzia Fides, 3/12/2024)