kmg.rw

by Stefano Lodigiani

Rome (Agenzia Fides) - In Rwanda, which in 1994 was struck by a tremendous genocide that reached the impressive figure of one million victims in a population of 6,733,000 inhabitants (44% Catholics), the Church and its members were not spared from the wave of violence and death that swept across the whole country (see Fides, 4/3/2024). “This is genocide, for which sad to say also Catholics are responsible,” emphasized Pope John Paul II before reciting the Regina Coeli prayer on Sunday, May 15, 1994, warning: “I would like to appeal to the consciences of those who plan and execute this violence. They are pushing the country to the edge of an abyss. All will have to answer for their crimes before history, and first of all, before God".

During the "Great Jubilee of the Year 2000", the Bishops of Rwanda held a liturgical celebration asking God to forgive them for the sins committed by Catholics during the genocide. On February 4, 2004, ten years after the genocide, the Rwandan bishops published a long message calling "not to forget what happened and therefore to promote truth, justice and forgiveness". "We have suffered greatly from being helpless witnesses while our compatriots suffered shameful deaths and were tortured under the indifferent gaze of the international community; we have also been deeply hurt by the involvement of some of our faithful in the murders," the bishops wrote , who thanked Pope John Paul II for his closeness during the genocide and his outcry to the international community. Recalling the massacres that were the result of unprecedented wickedness, the bishops called to "promote the unity of Rwandans" by asking everyone to "contribute to the preservation of truth and justice" and "asking for and granting the forgiveness that comes from God" .

Also on the day of the conclusion of the "Jubilee of Mercy" (8 December, 2015 - 20 November, 2016), the bishops published a letter, read in all churches, containing a new "mea culpa" for the sins of Christians during the genocide. As the President of the Rwandan Episcopal Conference, Monsignor Philippe Rukamba, Bishop of Butare, explained, "one cannot speak of mercy in Rwanda without speaking of genocide." The text reiterated condemnation of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi and all acts and ideologies related to discrimination based on ethnicity. During Rwandan President Paul Kagame's visit to Pope Francis at the Vatican on March 20, 2017, the first visit since the genocide, the Bishop of Rome "expressed the deep regret of the Holy See and the Church for the genocide against the Tutsi and renewed the appeal to God for forgiveness for the sins and failures of the Church and its members who have succumbed to hatred and violence and betrayed their evangelical mission".

As usual, the data on pastoral workers killed in 1994 were collected by Fides.

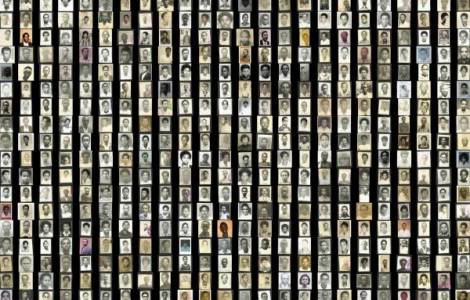

Missionary institutes (particularly the Missionaries of Africa, known as White Fathers, who began evangelizing Rwanda at the beginning of 1900), other religious congregations, dioceses, Catholic media were interviewed, in addition to verifying the scant information provided by the then Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples received from the Rwandan local church. These data indicate that there were 248 victims among church staff, including approximately 15 who died as a result of mistreatment and lack of medical care, and those missing who were never heard from again and were therefore presumed dead.

The list of pastoral workers murdered compiled at the time by Fides is reproduced here as an attachment at the end of this article. However, this list is undoubtedly incomplete, because it only takes into account bishops, priests, men and women religious and consecrated lay people. There are also seminarians, novices and a large number of lay people such as catechists, liturgical workers, employees of charitable organizations, members of associations that carried out a non-secondary role in the Church and in which a large number of Catholics, especially young people, were involved. In many cases, even the dioceses did not have reliable information about how many people in normal times ensure the life of the Christian communities scattered even in the most inaccessible places in the "Land of a thousand hills". Furthermore, in 1994, modern communication tools that allow planetary distances to be overcome in just a few seconds were not yet available.

Fides has regularly updated this dramatic list as it gathers news of the massacres and the bishops, priests and religious killed, as a look at the Fides news that appeared in print at the time shows.

According to the picture reconstructed by Fides, i three bishops and 103 priests (100 diocesan priests from all 9 dioceses of the country and three Jesuits) died violently in Rwanda in 1994; 47 friars from 7 institutes (29 Josephites, 2 Franciscans, 6 Marists, 4 Brothers of the Holy Cross, 3 Brothers of Mercy, 2 Benedictines and 1 Brother of Charity).

The 65 women religious belonged to 11 institutes: 18 Benebikira Sisters, 13 Sisters of the Good Shepherd, 11 Bizeramariya Sisters, 8 Benedictine Sisters, 6 Sisters of the Assumption, 2 Sisters of Charity of Namur, 2 Dominican Sisters of the African Mission, 2 Daughters of Charity, a Sister of the Help of Christians, of Notre Dame du Bon Conseil and a Little Sisters of Jesus.

There are also at least 30 lay people of consecrated life from 3 institutes (20 Auxiliaries of the Apostolate, 8 from the “Vita et Pax” institute and 2 from the St. Boniface Institute).

Thirty years after the genocide in Rwanda, we report below some testimonies from this tragic time, published by Fides: The atrocities in which some Catholics were also involved, there were also heroic actions by those who went so far as to sacrifice their own lives to save the lives of others.

'Whatever happens, we will stay here': Three bishops killed in Kabgayi

On June 5, 1994, three bishops were murdered in Kabgayi, along with a group of priests who accompanied them as they brought aid and comfort to those displaced by violence. They were the Archbishop of Kigali, Vincent Nsengiyumva, the Bishop of Kabgayi and President of the Rwandan Bishops' Conference, Thaddee Nsengiyumva, and the Bishop of Byumba, Joseph Ruzindana. In a letter written a few days before their deaths on May 31, they asked the Holy See and the international community to declare Kabgayi a "neutral city." A total of 30,000 displaced people, both Hutu and Tutsi, had gathered here and found refuge in Catholic institutions open to all without discrimination, such as the episcopal residence, parishes, monasteries, schools and a large hospital.

“Whatever happens to us, we will stay here to protect the population and the displaced,” they wrote in their appeal. Although they were given the opportunity to escape to safety, the bishops wanted to remain there because they believed that their presence would somehow protect the entire population, including refugees. But when they were placed under the protection of FPR (Rwandan Patriotic Front) rebels, they were murdered.

Other massacres attributed to members of the FPR followed in those days, including the one in Kigali in which some seventy people were killed, including ten religious who had gathered in a church with hundreds of other refugees.

"May the religious who disappeared with so many of their brothers and sisters who fell in the course of the murderous conflicts find forever in the Kingdom of Heaven the peace that was denied them in their beloved country," wrote Pope John Paul II in a message to Rwandan Catholics on June 9, 1994. "I pray to the Lord for the diocesan communities deprived of their bishops and numerous priests, for the families of the victims, for the wounded, for the traumatized children, for the refugees ", the Pope continued, asking all Rwandan residents and leaders of nations "to do everything possible to pave the paths of unity and reconstruction of the country so badly affected."

The first Mass celebrated in the place where his family was killed

Father Gakirage celebrated his first Mass at the site where his brothers were killed. This is the account he gave of his life and the moments that led to his ordination.

"I was born on November 14, 1960 in Musha, near Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, into a large and deeply religious family of the Tutsi tribe. Since my childhood, I have always felt a certain attraction to religious and missionary life. When I attended the minor seminary of my diocese, I was tested for the first time: the first conflict broke out between Hutu and Tutsi and many comrades were killed. I did not feel comfortable in the seminary because I had the impression that the priests did not adequately denounce these injustices while people outside were killing each other. Is this how I wanted to become a priest? I left the seminary and went to Uganda to study other subjects. I was about to begin medical school when I clearly felt the call of Jesus. I entered the Comboni Missionaries seminary and in 1990, after the novitiate, I went to Peru to study theology. Four years later I returned to my homeland to be ordained a priest. The ordination was supposed to take place in my country, but while I was in Rome I learned that my family had been murdered by a group of Hutu soldiers. This happened on the eve of my ordination, and everything changed for me. Since I was unable to return to Rwanda after this sad news, I traveled on to Uganda, where I was finally ordained a priest.

Because I wanted to know if anyone in my family had been saved, I tried to cross the border and get to Rwanda on the day of my ordination. My journey would not have been successful without God's providence. At the border I met the escort of Cardinal Roger Etchegaray, President of the Pontifical Council "Justitia et Pax", who was on an official visit to Rwanda on behalf of the Pope.

The next day, June 28th, some soldiers accompanied me to Musha. Upon arriving in my war-ravaged and devastated country, my first wish was to celebrate my first Holy Mass in these ruins. The thought that the place I was in was the same place where brothers and sisters and 30 young Tutsis had been murdered was painful. When I thought that I would no longer be able to find any living family members, I felt a deep sadness. However, when I looked at the stone that served as my altar, I was surprised to see three children: the two daughters of one of my sisters and the son of a cousin. They were the only survivors of a clan that consisted of 300 people before April 6th. I was overwhelmed and couldn't hold back the tears that welled up in my eyes. I calmed down, lifted my head, and continued the celebration thanking God that these three children had miraculously stayed alive.

In my first homily I spoke about the resurrection. They were not empty words or words of pity. I spoke of our resurrection, I said that we ourselves are our own resurrection. It's really difficult to point out this reality in the midst of so much death and destruction. It is like the weak flame of a candle that the stormy wind tries to extinguish."

The faith of Maria Teresa and Felicitas: "It is time to bear witness", "we will meet again in Paradise"

Maria Teresa was Hutu. She taught in Zaza. Her husband Emmanuel was Tutsi. He was a skilled worker at the school in Zaza. They had four children, three boys and a girl. On Sunday, April 10, Emmanuel went into hiding with his eldest son. “On Monday evening they came back to say goodbye to us,” said Maria Teresa. In fact, they were discovered and killed on April 12th. Maria Teresa learned the news from her parents, where she found refuge with her children after their house was looted. On April 14, four men came and took their sons to kill them.

Maria Teresa said she had to prepare her children: “My children, men are evil, they killed your father and your brother Olivier. They will certainly come after you, but don't be afraid. You will suffer a little, but then you will be reunited with your dad and Olivier, because there is another life with Jesus and Mary, and we will be reunited and we will be very, very happy." They picked up the children that same day and the witnesses said they were very brave and very calm.

Felicitas was 60 years old, Hutu and was the Auxiliary of the Apostolate in Gisenyi. She and her sisters welcomed Tutsi refugees into their home. Her brother, an army colonel in Ruhengeri, knew she was in danger and asked her to leave and avoid certain death. However, Felicitas replied to him in a letter that she would rather die with the 43 people she was responsible for than save herself. She then continued to save dozens of people by helping them cross the border.

On April 21, the militia searched for her and loaded her and her fellow sisters onto a truck that drove to the cemetery. Felicitas encourages the sisters: “It is time to bear witness”. They sang and prayed on the truck. In the cemetery, where mass graves were waiting, the militiamen, fearing the colonel's wrath, asked Felicitas to save herself, having already killed all 30 Auxiliary sisters of the Apostolate, but she replied: "I have no reason to live anymore after you killed my sisters." Felicitas was supposed to be the 31st victim.

The missionaries: amid brutality, fruits of faith also flourished

Father Jozef Brunner, of the Missionaries of Africa, White Fathers, shared the testimony of one of his confreres, who for many years was in charge of the Christian Community Leadership Training Center in Butare. “The ears and eyes of journalists did not notice something,” said the missionary, “the deeply rooted and lived faith of Christians, from the simplest to the most educated, the civil servants, the soldiers, who sacrificed their lives for their neighbor. To the same extent as the brutalities committed, acts of authentic heroism also developed. Certainly the church has found itself in the crosshairs of violence: her message of peace and unity was an obstacle for extremists. There is no other explanation for the fact that between four and six thousand people who had found refuge in churches and not in town halls were massacred. Several priests were killed trying to save these people. On television I saw eight of my students washing and caring for some abandoned children: that's how my students became my teachers."

The White Sisters recounted their experience by saying, “We witnessed the peace of God and the complete acceptance of his will shown in those who were led like a lamb to the slaughter.”

(Agenzia Fides, 13/4/2024)